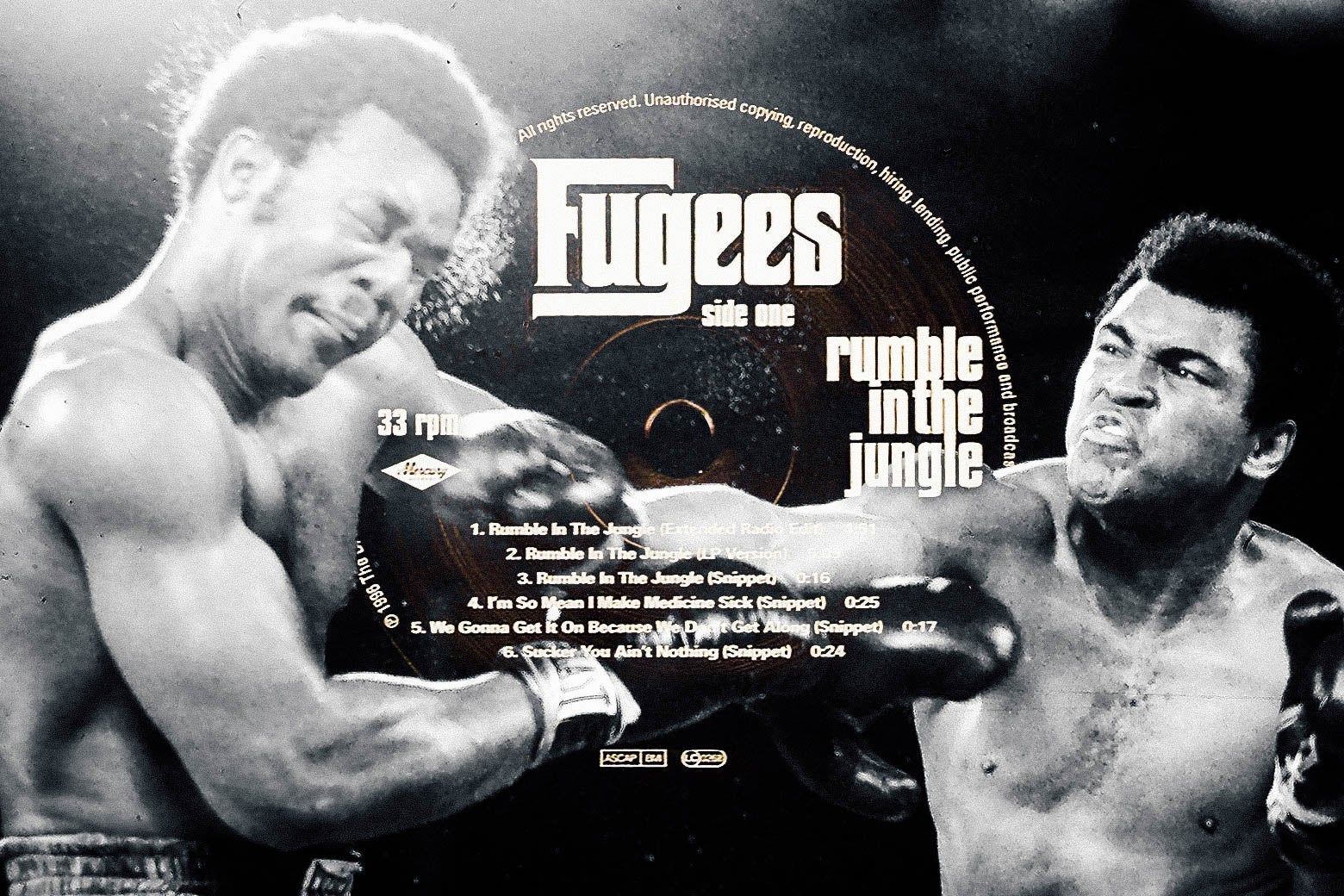

Decades after its release in 1996, the Muhammad Ali documentary When We Were Kings remains a dynamic, essential portrait of the legendary boxer. Recently released on the Criterion Collection, this official chronicle of Ali’s victorious fight against George Foreman in the 1974 Rumble in the Jungle captures the stirring presence of Ali and the excitement of the fight. Ali talks his shit and swings his fists; the camera sweeps through the landscapes of the nation then known as Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo); the boxing match is filled with thrilling fake outs and rope-a-dopes. Yet one of the best parts of When We Were Kings isn’t even technically in the movie—it’s “Rumble in the Jungle,” the movie’s credits-closing rap song, which runs right after George Plimpton signs off with a tribute to Ali’s poetic sensibilities. “Rumble” features an all-star cast of ’90s rappers at their peaks: the Fugees, John Forté, Busta Rhymes, and Q-Tip and Phife Dawg of A Tribe Called Quest. In five stirring minutes, the lyrical waxers and Ali superfans weave evocative verses recalling details of the Rumble, Ali’s Nation of Islam affiliation and dogma, his war opposition, and his fights against past opponents, as well as stark images of inner-city life. The song goes on throughout the scrolling text, fading out right when the screen goes black.

It’s a remarkable piece of music and, as a thorough exploration of Ali’s history and ideology, an ideal way to close out a biography of the great fighter. But “Rumble” also has a more important place in Ali’s legacy and the creation of When We Were Kings—in fact, according to some of the people behind the film, it was this very song and its creators that helped shape the direction of the movie and make it a singular portrait of Ali, a must-watch and essential marker of his legacy.

To understand why is in part to recall the zany, oft-told creation saga of When We Were Kings. Back in ’74, director Leon Gast was originally contracted to make a movie called Festival in Zaire, about the series of concerts taking place around the Rumble featuring artists like Miriam Makeba and the Spinners. After the festival turned out to be a disaster, the extensive footage of both the musicians and the Rumble would lay in creative purgatory for decades, following a dearth of financing and a battle for ownership rights. Still, Gast and his lawyer David Sonenberg never gave up on their effort to get the film released.

Then, Sonenberg serendipitously happened upon the creative spark that would get the Ali footage out. In the early ’90s, he was alternately working on the film and managing various music groups, including the Fugees, the rap trio consisting of Lauryn Hill, Pras Michel, and Wyclef Jean. This was Sonenberg’s first experience with a hip-hop posse, and as he recalled to me, he would not only learn much from them about the burgeoning musical genre but about Muhammad Ali as well.

“One day, maybe around ’93 or ’94, Wyclef Jean had come to see me to talk about some Fugees business,” Sonenberg says. “I was upstairs working on the editing of the film. And he walked in and watched some of the footage on the screen, and I remember him saying: ‘Yo, man! That’s Muhammad Ali! He’s the original rapper!’ ” Sonenberg had never thought of Ali in those terms, and the comment convinced him to focus the film further on its standout figure. “We had 400 hours’ worth of film, and most of the focus was to follow through on that original concept” of the music festival, Sonenberg says. “With the passage of time, and so many things having happened to Ali, it became clear to me that we should make this the Muhammad Ali movie, and not Festival in Zaire. … We had already focused on [Ali] a lot. But I think that, once we got in our head that Ali was the original rapper, that changed things dramatically.”

But not only did Jean’s comment change the direction of the film—it became a means of selling Ali to a younger generation. Rappers, at the vanguard of youth culture, had already been shouting out Ali in their rhymes for years. In Sonenberg’s head, this became key. “I asked [Wyclef] if he would be interested in putting together a song that we might be able to include in the film,” he says. “I had suggested the title ‘Rumble in the Jungle.’ That was our working title for our movie for a long time, but ultimately we had changed the movie title to When We Were Kings. But I thought ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ would make for a great rap song.” Jean immediately dived into it, wrangling the rest of the participants on board and co-producing the track with Lauryn Hill.

As amazing as the result was, the song wouldn’t fit too well within the film itself—much of the music in the Zaire festival and included in the documentary consisted of B.B. King’s guitar solos and James Brown’s iconic grunts. So even though the song had to be shunted off to the credits, Sonenberg wanted it to represent the movie as much as possible: The rap connection could help rope in a broader audience. If he could prove to Hollywood that younger viewers were interested in Ali, Sonenberg recalls, “that would help me get When We Were Kings into a much broader, mainstream distribution, rather than the way documentaries were normally distributed at that time—distributed in a few art houses.”

Famed trailer editor Mark Woollen put together a promotional reel for the movie and used the song within. Because Sonenberg liked how it turned out, he also asked Woollen to direct and edit a music video for “Rumble” along with Marc Smerling, who’d already worked with the Fugees. The whole shoot was put together in one night: The artists were all performing the song together for the first time ever, and a custom boxing ring was built just for the occasion, tucked into an alleyway in the Dumbo neighborhood of Brooklyn and subsequently torn down after filming. Yet the result is spellbinding: The artists circle around the ring and throw boxing glove–clad fists at the camera, unrelenting and fierce. As Woollen says, the video was shot and edited in a way to parallel the fight itself: Each artist comes out for their own individual fight round, leaping around the ring Ali-style, while the video cuts to film scenes during shoutouts to figures like Foreman and Zaire’s onetime dictator Mobutu Sésé Seko. The vibe, according to Smerling, was meant to be “the Rumble in the Jungle meets Raging Bull.”

With all this promotional effort, the song found its audience. “I was hearing it everywhere,” Smerling says. In the U.K., the song shot up to No. 3, and it was also popular in Germany and Ireland. In the U.S., the video received plenty of play on MTV, according to Smerling and Woollen. The When We Were Kings soundtrack peaked at No. 64 on the Billboard charts, and the song hit the Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay chart. When the official movie premiere was held at Radio City Music Hall in February 1997, with a star-studded guest list and appearances by both Ali and Foreman, “Rumble in the Jungle” was performed live, and Ali himself went up to join the rappers onstage. The Fugees and Q-Tip and Phife and Forté and Busta also did the song on The Late Show With David Letterman, in an energetic showcase that featured them coming out one by one per their verses and backing one another’s lines. (Sadly, no boxing ring was constructed inside CBS Studios.) The movie, of course, became a huge success by doc standards, earning nearly $3 million at the box office and going on to take home the Oscar for Best Feature Documentary in 1997.

Yet decades after, even though When We Were Kings is still hailed as a classic (and is experiencing a bit of a resurgence, with the Criterion Collection edition as well as a theatrical adaptation in the works), the memory of “Rumble in the Jungle” itself is somewhat neglected. The soundtrack album for Kings is out of print, and you can’t stream the song anywhere other than YouTube (and as Sonenberg told me, there are currently no plans to feature the song within the musical version). It’s a shame, for “Rumble” is a significant chapter in rap history, film history, and sports history, a shrine to Ali that helped promote an even bigger one. It was the Fugees’ last major song, as all the members imminently went on to solo careers—afterward, their only releases together as a group were a song for a Sesame Street special and a leaked single in 2005. But “Rumble” continued to live through other musical reincarnations: The song was remixed by Detroit legend J Dilla, in a version later released as part of a posthumous Dilla tribute on a 2011 mixtape by producer J. Period. Today, rappers continue to not only reference Ali in their verses but devote entire songs to his legacy, yet few of those tracks compare to “Rumble.” What it does best, as a song, is bolster Ali as a figure not so easily bound by time but eternal, showing how a fighter of an entirely different era could remain such a transcendent figure decades later. We have the rappers to thank for helping to keep Ali’s legacy alive.