Wells Fargo “collected millions of dollars in fees and interest to which [it] was not entitled, harmed the credit ratings of certain customers, and unlawfully misused customers’ sensitive personal information,” according to the Justice Department, which announced on Feb. 21 that the banking company has agreed to pay an additional $3 billion to settle potential charges stemming from its unauthorized creation of several million customer accounts between 2002–16. Fees and penalties in relation to this scam alone had already totaled more than half a billion dollars.

Good news, right? That looks like accountability, and $3 billion is a lot of dough. But that $3 billion represents only a small part of the bank’s takings from just this one scam—including customer money to which, by its own admission, it “was not entitled.”* From that perspective, the DOJ basically caught a gang of thieves and let them scoot right back to their den with most of the loot. Worse still, criminal prosecutions—for a bank that openly admits it stole money from its own customers—are off the table for now: “The criminal investigation into false bank records and identity theft is being resolved with a deferred prosecution agreement in which Wells Fargo will not be prosecuted during the three-year term of the agreement.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, whose incisive and relentless questioning led to the resignations of not one but two Wells Fargo CEOs in connection with the scam, was not impressed with the announcement.

“The Justice Dept & SEC’s settlement with Wells Fargo barely puts a dent in the bank’s $12 billion profits from the fake accounts scam,” she tweeted. “When big banks can break the law, pay a fine, consider it the cost of doing business, & go back to life as normal, nothing changes. Nothing.

“I got [former CEO John] Stumpf fired,” she concluded, “but he’s probably popping champagne tonight.”

Warren has been fighting Wells Fargo’s misdeeds for more than a decade, as she reminded Nevadans at the Democratic primary debate on Feb. 19, harking back to a 2008 meeting with Las Vegans who’d lost their houses in the mortgage crisis.

“When Mayor Bloomberg was busy blaming African Americans and Latinos for the housing crash of 2008, I was right here in Las Vegas, literally just a few blocks down the street, holding hearings on the banks that were taking away homes from millions of families,” she said. “That’s when I met Mr. Estrada, one of your neighbors. … He thought he’d done everything right with Wells Fargo, but what happened? They took away his house in a matter of weeks.”

Wells Fargo paid $5.35 billion as its part of a five-bank, $26 billion settlement to provide relief to American homeowners harmed in the mortgage crisis. According to the New York Times, Mr. Estrada and 750,000 people like him would be compensated for the loss of their homes with checks for $2,000.

This struggle for accountability is not over. The New York Times reported Wednesday that the U.S. House of Representatives Financial Services Committee will hold hearings next week on the failure of Wells Fargo to comply with its existing regulatory settlements. [Update, March 9, 2020, at 8:20 a.m.: Wells Fargo announced Monday morning that its board chair, Elizabeth Duke, and another board member, James Quigley, had resigned from the company.]

It’s hard to believe that so much thieving has gone unpunished and unchecked for so long. But Wells Fargo has powerful and respected champions who have steadily turned a blind eye to criminal activity, perhaps because they have made a lot of money from it.

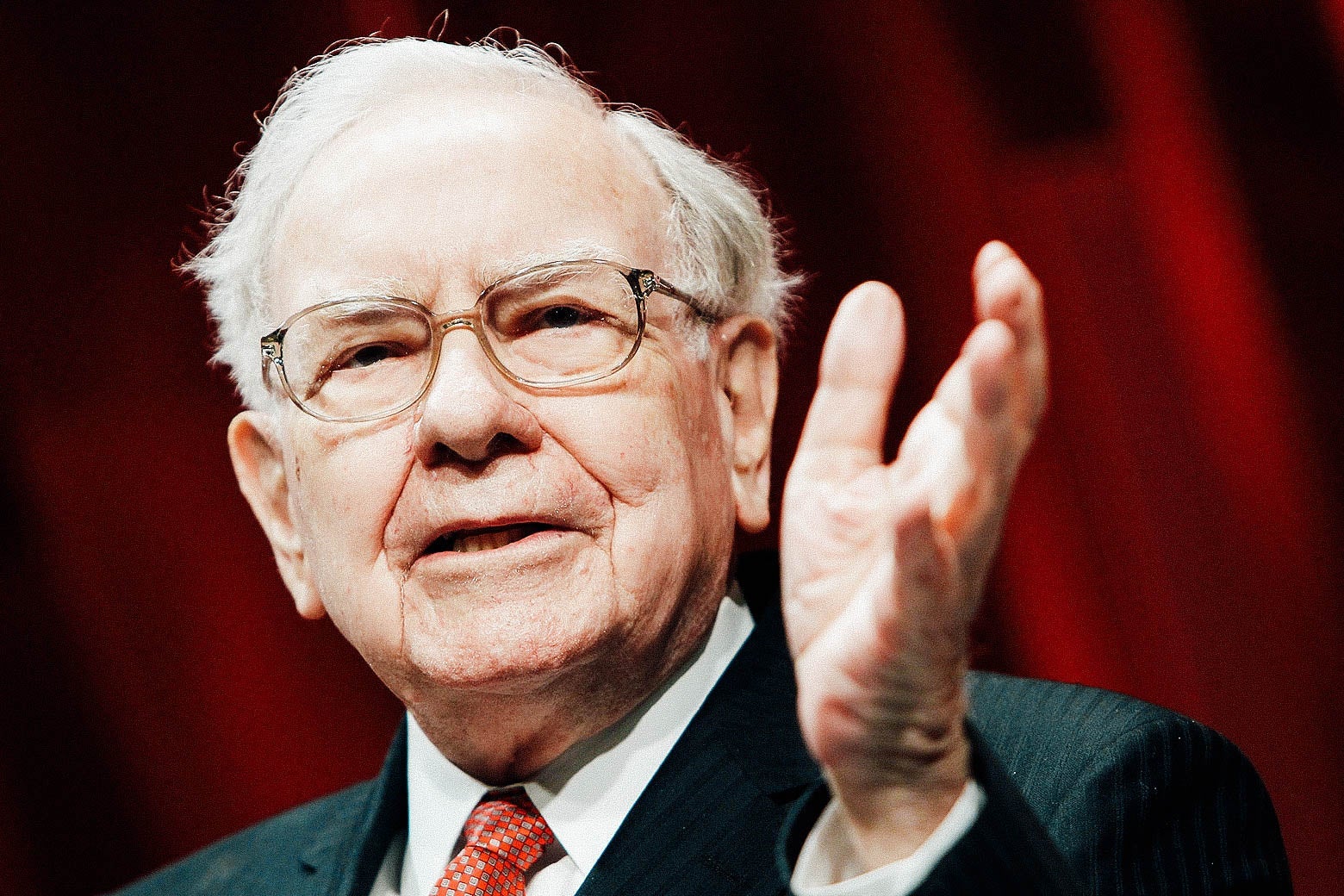

One of the bank’s chief champions is legendary investor Warren Buffett, whose conglomerate, Berkshire Hathaway, is Wells Fargo’s largest shareholder. The highlight of the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholders’ meeting in Omaha, Nebraska, comes when Buffett and his vice chairman, Charlie Munger, take questions from their adoring fans, tens of thousands of whom attend the event each year.

The questions tend to be friendly, but at the most recent shareholders’ meeting last May, a retired police officer named Mike Hebel asked Buffett a question about Wells Fargo. Hebel wanted to know why Berkshire, the company he trusted with his own savings, was invested in a bank that has been helping itself to its customers’ money with persistent enthusiasm for the past 20 years or more.

Buffett is easily the most beloved figure in American business. The Sage of Omaha, as he is known, is the face of good capitalism in America, an exemplar of the old-fashioned values of foresight, integrity, leadership and success. His company has a market cap of more than half a trillion dollars and as of last November boasted the largest hoard of cash held by any U.S. corporation: $128 billion. Berkshire is also the biggest publicly traded financial services company in the country, and its 7.82 percent stake in Wells Fargo is currently worth just under $12 billion, a drop of 22 percent since Feb. 17.

Hebel’s question was:

The Star Performers Investment Club has 30 partners, all of whom are active or retired San Francisco police officers. Several of our members have worked in the fraud detail, and have often commented after the yearslong fraudulent behavior of Wells Fargo employees—should have warranted jail sentences for several dozen, yet Wells just pays civil penalties and changes management.

As proud shareholders of Berkshire, we cannot understand Mr. Buffett’s relative silence compared to his vigorous public pronouncement many years ago on Salomon’s misbehavior. Why so quiet?

Here was an ordinary investor, a cop, who—despite having made money on his Berkshire investment—noticed that something very wrong was happening at Wells Fargo, and demanded ethical and legal accountability from a couple of the country’s most famously admired and trusted, most apple-pie-American billionaires. Buffett responded at length, with several zingers:

At Berkshire … we have 390,000 employees, and I will guarantee you that some of them are doing things that are wrong right now.

And:

Wells has become, you know, exhibit one in recent years. But if you go back a few years, you know, you can almost go down—there’s quite a list of banks where people behaved badly.

And:

I don’t really have any inside information on it at all. … I don’t know the specifics at Wells.

That was interesting, because there were plenty to know. The House Financial Services Committee had held hearings about these very specifics only a few weeks before that shareholders meeting. The hearings, called “Holding Megabanks Accountable: An Examination of Wells Fargo’s Pattern of Consumer Abuses,” went poorly for the bank, and CEO Tim Sloan had stepped down shortly afterward.

The scandal would continue to snowball. Last month, banking regulators reported that John Stumpf—Sloan’s predecessor, whose nose Warren bloodied so effectively back in 2016—agreed to pay $17.5 million of his own money in fines for his part in the fake accounts scandal; he is barred for life from working for or even serving on the board of a bank. Multiple Wells executives are facing further investigation, fines, and potential criminal charges.

This fiasco is costing the bank far more than just fines and penalties. Last month the Wall Street Journal revealed that Wells’ wealth management division, which employs 13,000 financial advisers, has been hemorrhaging these valuable employees since the fake accounts scandal broke. Financial headhunter Brian Hamburger told the Journal, “Advisers tell me they don’t want to have to apologize for the firm they work for.” Yes, and maybe they also have little appetite for the task of persuading investors to entrust their funds to known swindlers.

But back at the shareholders meeting last May, Charlie Munger was saying: “I don’t think people ought to go to jail for honest errors of judgment. It’s bad enough to lose your job. And I don’t think that any of those top officers was deliberately malevolent in any way. … I don’t think Tim Sloan even committed honest errors of his judgment. … I wish Tim Sloan was still there.”

“Yeah, there’s no evidence that he did a thing,” said Buffett. “But he stepped up to take a job that—where he was going to be a piñata, basically, for all kinds of investigations.”

One might be forgiven for thinking that the head of a bank that has been stealing money from its customers might reasonably expected to take a whack or two. Or maybe the real piñatas were the thousands of Wells Fargo employees who wound up losing their jobs for doing exactly as their bosses asked.

The wildest part of Buffett’s answer to Hebel came at the end.

“I actually proposed … that if a bank gets to where it needs government assistance, that basically the responsible CEO should lose his net worth and his spouse’s net worth,” he said. But he failed to mention that this brain wave came in the context of being grilled by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission on the 2008 banking crisis. He was proposing personal liability for CEOs as a preferable alternative to creating stronger banking regulations. “Maybe the spouse would do better policing than the regulator,” he cracked. Tee-hee.

But Hebel was not asking Buffett and Munger how Berkshire Hathaway felt about individual acts of wrongdoing at Wells Fargo. He was asking why its money—his money—was sustaining a bank whose misbehavior was clearly deeper, worse, and more ingrained than the crimes of a few people. The barrel is plainly rotten, in other words, not just a few apples. A better question than Mike Hebel’s is: Why hasn’t this bank been shut down?

In March of 2019, just before the House hearings, Yahoo Finance made a “complete timeline” of 19 Wells Fargo scandals going back to the fall of 2016. But LOL, no, Yahoo’s timeline was not remotely “complete.”

Here’s a selection of the misdeeds for which Wells Fargo has been penalized by various agencies over the past few years:

• overcharging service members for loans, and then

• illegally repossessing their cars

• failing to file reports on suspected money laundering activity

• failing to obey regulations for bankruptcy planning

• charging auto loan customers for duplicative insurance without their knowledge

• keeping conveniently mum to investors about the incipient fake account scandal

• encouraging retail investor churn in high-fee products

• deliberately originating mortgage loans with false income information

• taking punitive action against whistleblowers in its own company.

Good Jobs First’s Violation Tracker lists 136 separate fines and penalties paid by the bank since 2000, totaling about $17.3 billion.

What percentage of the loot illegally acquired by Wells Fargo in this 20-year crime spree does that $17.3 billion in penalties represent? Ten percent? A tenth of a percent? Who knows? Put it this way: The bank’s confessed 2019 Q2 profit, reported in July, rose to $6.21 billion, compared with $5.19 billion the previous year. Even with its retention problems, its wealth division recently reported $1.9 trillion in customer assets under management.

New and terrible details of the fake accounts scandal emerged in the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s filings on Jan. 23 against former executive Carrie Tolstedt and others, documenting a work environment so toxic and hateful as to stun even those of us who had already understood its broad outlines. The filings quote many Wells Fargo employees’ written pleas to their deranged, abusive bosses:

Surely, you must be aware that you will reach a sales number to be achieved that will force the staff to cheat to obtain it.

The noose around our necks ha[s] tightened: we have been told we must achieve the required solutions goals or we will be terminated. This type of practice guarantees high turnover, a managerial staff of bullying taskmasters, [and] bankers who are really financial molesters [and] cheaters.

Despite this, nobody in charge has been indicted, let alone convicted, for the crimes of Wells Fargo, so there obviously hasn’t been much of a deterrent for committing them. Shareholders, all of them shielded from direct liability, also benefited, as millions of Wells Fargo’s own customers—and employees—were persistently fleeced and abused.

Unless you are one of them, it may seem to have nothing to do with you, what these kazillionaire bankers are up to. But what Wall Street and the banks are doing is deep in your life, through and through. It’s where you’re keeping your money! A little bit of the sweat of your brow goes in their pocket with your every paycheck.

“There are decisions about what we want not just our economy to look like, but also our broader world to look like, that come from what giant banks decide that they are going to finance.” Graham Steele, a former legislative assistant to Sen. Sherrod Brown, told me.

What is the true cost of accepting the aw-shucks evasions of people like Warren Buffett? Wealth should not be so admired that it automatically sanitizes the people who hold it, and their deeds, placing them beyond the reach of interrogation.

It bears mentioning that despite their protestations of executive innocence, Buffett and Munger quietly sold off 55.2 million shares of Wells Fargo in the fourth quarter, about 15 percent of their holdings. This move left Berkshire still the bank’s largest shareholder, but barely. A cynic might observe that dumping enough to drop behind second-place Vanguard’s stake might attract unwelcome notice in the market.

What would it take to stop a bank that refuses to stop itself?

Since the 2008 crisis, financial institutions have become punching bags to some, but most people are still perfectly happy to keep their money in big banks. Banks are convenient places in which to have your paycheck deposited, and it’s convenient, too, to have plenty of ATMs around; one is rarely invited to consider that the people running the place might be literal thieves and bad guys, or that you should keep your money elsewhere, or that a bank should just be shuttered.

“We have the tools to break up Wells Fargo or any miscreant bank right now,” David Dayen, executive editor of American Prospect, author of Chain of Title, and a longtime reporter on financial shenanigans, told me over email. “The Federal Reserve can do it, or the FDIC. Corporations are granted a public charter by governments with the implicit (and often explicit) intention that they act in the public interest. A bank that violates that charter repeatedly should simply lose it. Wells Fargo should have been given the corporate death penalty long ago.”

State attorneys general, too, have the power to revoke a corporation’s charter, as Dayen pointed out in the New Republic: In Delaware—where more than half of all publicly traded U.S. corporations are domiciled—if the state attorney general finds a corporation has “abused or misused” its charter, they can just mosey on over to the Court of Chancery and direct the court to shut it down.

And finally, if governments or regulators can’t or won’t compel a bad bank to stop stealing, people really can just get their money out and put it somewhere else. Banks can’t make loans without a certain percentage of deposits held by law as “reserve requirements.” Should deposits take a big enough hit, even the largest bank could be forced out of business by its own depositors. It’s a lot of trouble to change banks, no doubt; on the other hand it is also quite unpleasant to be ripped off incessantly by a load of Brioni-suited crooks.

After Sen. Elizabeth Warren mopped the floor with onetime Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf in a Banking Committee hearing in 2016 (“Have you returned one nickel of the millions of dollars that you were paid while this scam was going on?” she asked—and he hadn’t, until he was forced to, years later), Stumpf retired, as did Tolstedt, who had been head of the community banking division. Tolstedt, who is reportedly still fighting charges, has so far taken the brunt of the blame for running the fake accounts fraud scheme, and misleading the board, after an internal investigation. Five thousand three hundred Wells employees lost their jobs in the wreckage.

A lot of hay was made in the press over the $136 million eventually clawed back from Stumpf’s and Tolstedt’s golden parachutes, but Fortune reported that Stumpf still left the company with $105 million—the clawback amounted to a 40 percent hit on his retirement package—while Tolstedt’s took a 54 percent hit, leaving her with a $57 million exit. That is to say, even after his $17.5 million speeding ticket, Stumpf’s exit package alone was still worth $87.5 million.

The precedent for rewarding thieving bankers was fixed in the years after 2008, when, instead of being prosecuted, many of those responsible for the mortgage crisis were bailed out and made whole by the Obama administration, even as millions of ordinary Americans lost their houses, jobs, and pensions.

“The message in the crisis itself was you can crash the global economy, and you will get bailed out,” Steele told me. “So we’ll do some marginal reforms, and then you can take millions and millions of people’s homes away, mostly fraudulently. And there’ll be no accountability for that either.”

This pattern of showering people with money in exchange for corporate malfeasance repeated itself many times over the next decade at Wells Fargo.

Tim Sloan, Stumpf’s replacement, was a company veteran of nearly three decades who had served Wells as CFO and COO. With each new scandal, he publicly promised reforms and transparency. It’s unclear whom he thought he was kidding. The scandal machine rolled on unhindered throughout his tenure.

In August of 2019—that is, just months ago—a new scandal emerged: Wells had been charging overdrafts to closed bank accounts. A single whistleblower reported having personally nabbed about $100,000 in such fees on behalf of the bank over an eight-month period. Sen. Warren demanded answers from the bank on Aug. 19. (Uh, looking into that we’ll get back to you, it replied, more or less).

Warren’s popularity grew in no small part because of the effectiveness and vim with which she socked it to Sloan in October 2017, as she had to Stumpf before him. “At best you were incompetent. At worst you were complicit. And either way, you should be fired,” she yelled, thrillingly. Even so, Sloan managed to hang on until last March. His compensation for 2018 was $18,426,734. Maybe he thought that wasn’t such a lot, given what his old boss walked away with. Remember, if you have a bank account at Wells Fargo, a bit of that is your money.

Wells’ new CEO, Charles Scharf, started work last October; he’s its fourth leader in three years. His job is to rehabilitate the bank’s tarnished reputation, but until quite recently, Scharf didn’t seem to think anything much needed fixing (and no wonder; the Washington Post reported that “in 2020, Scharf will have a target annual pay package of $23 million and receive a one-time make whole award of $26 million for money he lost by leaving Bank of New York Mellon,” and if you want to rewind for a moment over the phrase “money he lost,” I won’t blame you). Scharf “dismissed the notion that Wells needed a change in structure or strategy,” according to the FT in late September. “The business model is fundamentally sound,” he said.

Scharf’s tone changed dramatically after Stumpf was made to pay even a fraction of Wells Fargo’s ill-gotten gains out of his own pocket.

“The OCC’s actions are consistent with my belief that we should hold ourselves and individuals accountable,” he declared in a statement to employees. “They also are consistent with our belief that significant parts of the operating model of our Community Bank were flawed,” he added.

The altar-boy routine continued on Feb. 21, after the DOJ announced its settlement. “The conduct at the core of today’s settlements—and the past culture that gave rise to it—are reprehensible and wholly inconsistent with the values on which Wells Fargo was built,” Scharf said, in a thoroughly incoherent statement. “We are committing all necessary resources to ensure that nothing like this happens again, while also driving Wells Fargo forward.”

Scharf’s newfound chagrin makes a sound argument for relieving criminal executives of all their ill-gotten gains, as Warren Buffett once suggested, and also putting them in jail, even if the current administration has insufficient brains, integrity, or political will to shut the Wells Fargo supercrime bonanza down completely. But the real lesson of Wells Fargo is that punishing a lawless CEO or two is not enough. Sometimes criminal institutions just need to be annihilated.

Correction, March 11, 2020: This article originally described the bank’s takings from the scam as customer money; the $12 billion figure used by Elizabeth Warren included other sources of income along with the money that came directly from the customers.