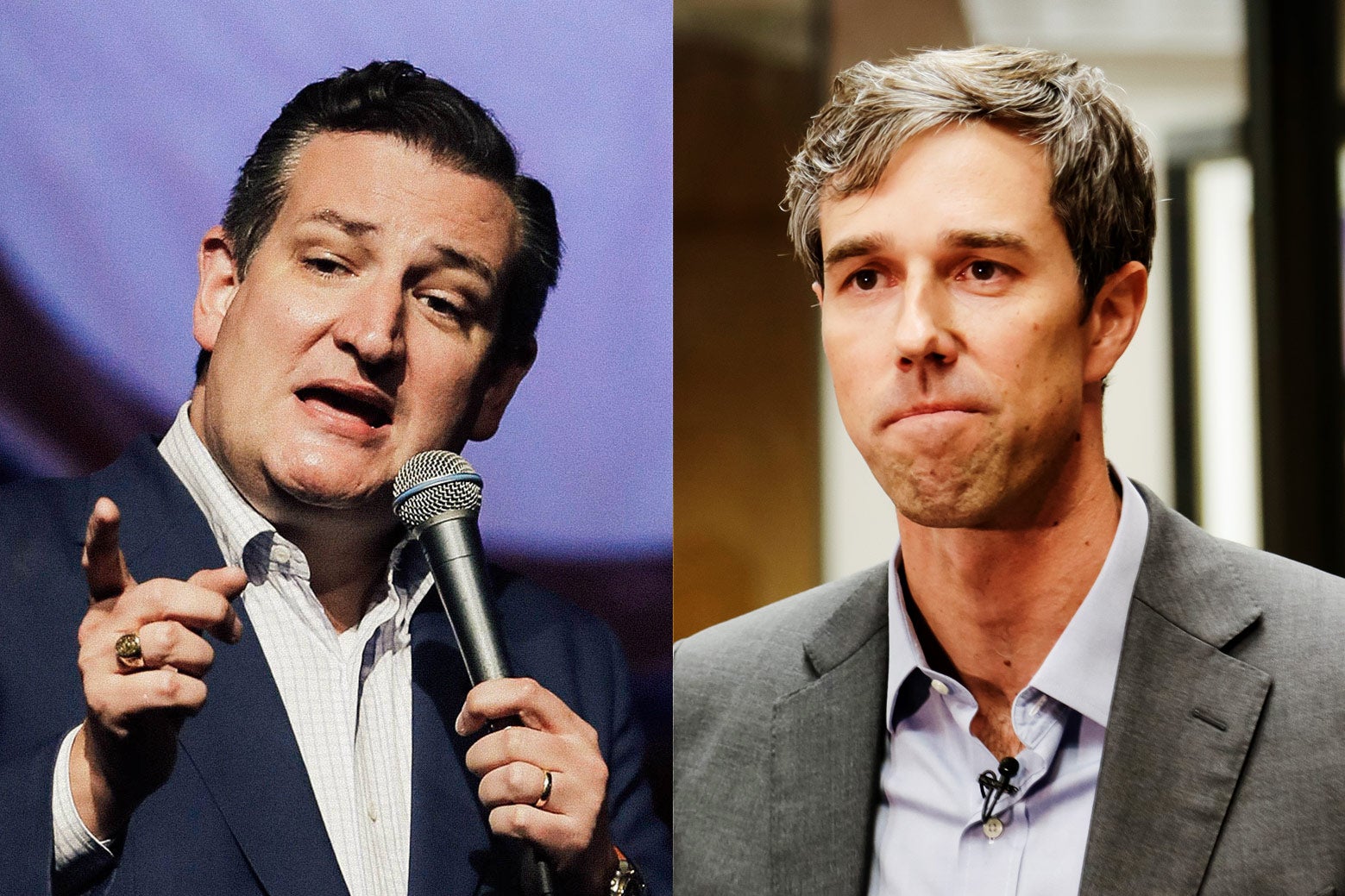

It’s mid-April, and a reputable pollster is already declaring that the Senate race between Democratic Rep. Beto O’Rourke and Republican Sen. Ted Cruz in Texas is “too close to call,” at 47 percent to 44 percent. It’s Quinnipiac’s first poll in Texas, and the first major poll of one of the most closely watched races in the country.

It’s also very hard to believe.

One can acknowledge that an April poll of registered voters, weighted under certain conditions, shows a close race. And there’s no reason for the Cruz campaign to love this number. But such an early poll, along with all of the glowing tributes to O’Rourke, have built up expectations that will be extremely difficult for O’Rourke to meet in November. Though O’Rourke is positioned to post the best statewide showing for a Texas Democrat in years and could conceivably win, the task is far more uphill than national fascination with the El Paso progressive suggests.

The gap between potential and likely voters in Texas is vast, and it’s particularly vast for the voters O’Rourke is relying on. Quinnipiac’s poll is weighted to the demographics in the state’s Census count, as is “protocol” for these early polls of registered voters, James Henson, director of the University of Texas–Austin’s Texas Politics Project, told me on Wednesday. That likely means that it over-counts Hispanic voters. Henson has seen this story before. “In Texas, Hispanic turnout—and therefore Democratic turnout—is always lower than the weighted sample,” he said in an email. “It’s a standard dynamic here.”

The poll also showed noticeably liberal preferences among independents, even though Texas independents tend to be more right-leaning. Independents in Texas supported Trump over Clinton by 14 percentage points in 2016, according to exit polling, but the Quinnipiac poll found only 28 percent of independents in Texas approve of Trump compared to 64 percent who disapprove. Either that group is re-aligning fast, or a demographically weighted sample of registered voters isn’t giving a crisp preview of likely voter turnout in November.

“The particular confluence of voter turnout, state demographics, and party identification in Texas in recent history meant that Democrats at the top of the state ticket generally poll much better in April than they do in the vote count in November,” Henson said.

Texas political experts with whom I’ve discussed the race over the last few months—regardless of their position on the political spectrum—all express exasperation at the breathless coverage of O’Rourke’s bid, which treats his grass-roots campaign against Cruz almost as prophecy awaiting certain fulfillment.

The hype reached its first crescendo ahead of the March 6 primary. Early voting for Democrats had surged, especially in major metropolitan areas. In the top 10 most populous counties, early Democratic voting more than doubled while Republicans’ share increased only marginally.

But then Election Day came, and Republicans showed up. More than 1.5 million Republicans, or 10.12 percent of registered voters, voted in the Republican Senate primary, while just over 1 million, or 6.8 percent of registered voters, voted in the Democratic Senate primary. That’s a vast improvement on Democratic turnout from the 2014 Senate primary, when just over a half-million Democrats showed up compared to Republicans’ 1.3 million. But to double one’s primary turnout and still only comprise about 40 percent of total votes should have been a cooler of ice water on the regurgitated narrative about how Texas is ready to turn blue any minute now. Democrats made progress. There are still more Republicans.

“At the end of the day, yesterday was more or less a regular Texas election,” Texas Tribune editor Evan Smith told Vox the day after the primary. “More Republicans turned out than Democrats.”

While Cruz received 1.3 million, or 85 percent, of the vote in his primary, O’Rourke, who represents El Paso in the state’s westernmost district, picked up just over 641,000 votes, or 62 percent of primary votes.* More worrisomely, he lost dozens of border counties to a virtual unknown, Sema Hernandez. That’s not necessarily a sign of antipathy from Democratic primary voters, but it does raise questions about whether O’Rourke can break the cycle of underwhelming Latino turnout. O’Rourke’s campaign noted that some voters who may support him in the general election might have voted in the Republican primary, because they may live in red-enough areas where down-ballot primary races are, effectively, the general election.

The Quinnipiac poll reinforces how much work remains in O’Rourke’s long quest to introduce himself to voters statewide, let alone persuade them. Even after a year of campaigning, he survey showed that 53 percent of registered voters hadn’t heard enough about O’Rourke to form an opinion. The good news for O’Rourke is that he has raised the oceans of cash necessary to make that introduction. The bad news is that the Cruz campaign and its super PAC allies will surely be spending substantial sums, too, to define O’Rourke in a much different light.

The overhyped media coverage leading into the primary obscured the real gains Democrats might be making in the state. “If you strip away the unrealistic expectations, this will probably be a good cycle for the Democrats, one of the best they’ve had in a long time,” Henson said. “But it’s kind of hard to write a headline, to build a narrative, whether you’re a reporter or a Democratic fundraiser or candidate recruiter that says, ‘Democrats: Inching Back from Near Death.’ ”

And inching back from near death is a far cry from beating Ted Cruz.

Cruz is often mocked for—how shall we put it?—his lack of charisma or spontaneous charm. But that’s not the worst trait when you’re a Republican running for re-election in a red state. He is a formidable campaigner with a formidable team. I’m not sure Cruz has ever said a word that wasn’t carefully considered, and that’s a problem for O’Rourke: Cruz does not make the sort of boneheaded errors that can open the door to a long-shot candidate.

The Cruz campaign sees Texas as rigidly red with few persuadables among likely voters.

“Basically every quarter, we score the voter file … using predictive analytics and a series of algorithms we built out over the state of Texas going back to 2012,” Cruz’s pollster, Chris Wilson, told me in an interview shortly after the primary. “And every quarter, the file is more Republican than it was the prior quarter.”

To give you a sense of the granularity through which the Cruz campaign is looking at the data and targeting voters accordingly, Wilson, who’s also the pollster for Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, shared a figure with me.

“I’ve already built out the models for the fall, the general election,” he said. “And I can tell you that as of today, there are exactly 2,068,746 voters in Texas that do not currently plan to vote, but if they did vote, would vote for Greg Abbott. And they’d vote Republican.”

In order to win, O’Rourke needs to accelerate one aspect of very recent Texas political history—Republicans’ weakening in major metropolitan areas—and defy the low-turnout trends that have doomed other recent, initially optimistic efforts to “turn Texas blue.”

For the former, as Henson put it, O’Rourke needs to “hasten the decay” in the “inner suburban rings where there are some signs of the decay of previous Republican advantages.” That decay, he says, is probably “slightly more prosperous minority voters that you want to get to vote,” along with swaying “upper-middle-class Latinos that are voting Republican.”

I asked him about another demographic that Democrats are always eager to predict as a just-around-the-corner en masse defection from Donald Trump’s GOP: Republican women. Henson shared with me some recent polling results of Republican women that showed only 29 percent of them had a favorable opinion of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and that a plurality felt the recent attention towards sexual harassment was leading to the unfair treatment of men. Similarly, only 17 percent viewed the #MeToo movement favorably.

“Republican women are not very persuadable,” Henson said.

If O’Rourke can turn out the purpling inner suburbs of cities like Dallas and Houston, then it’s a matter of turning out the rest of the state’s dormant Democratic populace in a way that hasn’t been done anytime recently. Texans are cynical that this will happen.

“I believe there are probably enough people who identify as Democrats or progressives in Texas that if they all turned out to vote, you’d have competitive elections,” Evan Smith said in the Vox interview. “And if I were 6 foot, 8 inches, I’d be playing basketball for the New York Knicks.”

I’m inclined to believe those whose full-time job is to study Texas politics and who are mystified at why O’Rourke is given a credible chance to beat Cruz. But sometimes, when you’re so deep in the weeds of recent evidence, and so jaded from previous overhyped efforts, you find yourself looking at a paradigm shift only after it’s happened. FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver made a useful comparison to another recent election where the pros who’d managed the turf for decades thought they had the voting patterns nailed, down to a person.

“I think I’m on team Cruz-could-actually-lose,” Silver tweeted. “The arguments to the contrary remind me a little too much of the arguments that Democrats could never lose a presidential election in Pennsylvania.”

*Correction, April 20, 2018: This story initially misstated the number of votes Beto O’Rourke received in the Democratic primary for U.S. Senate. He received just over 641,000 votes, not 6.4 million.