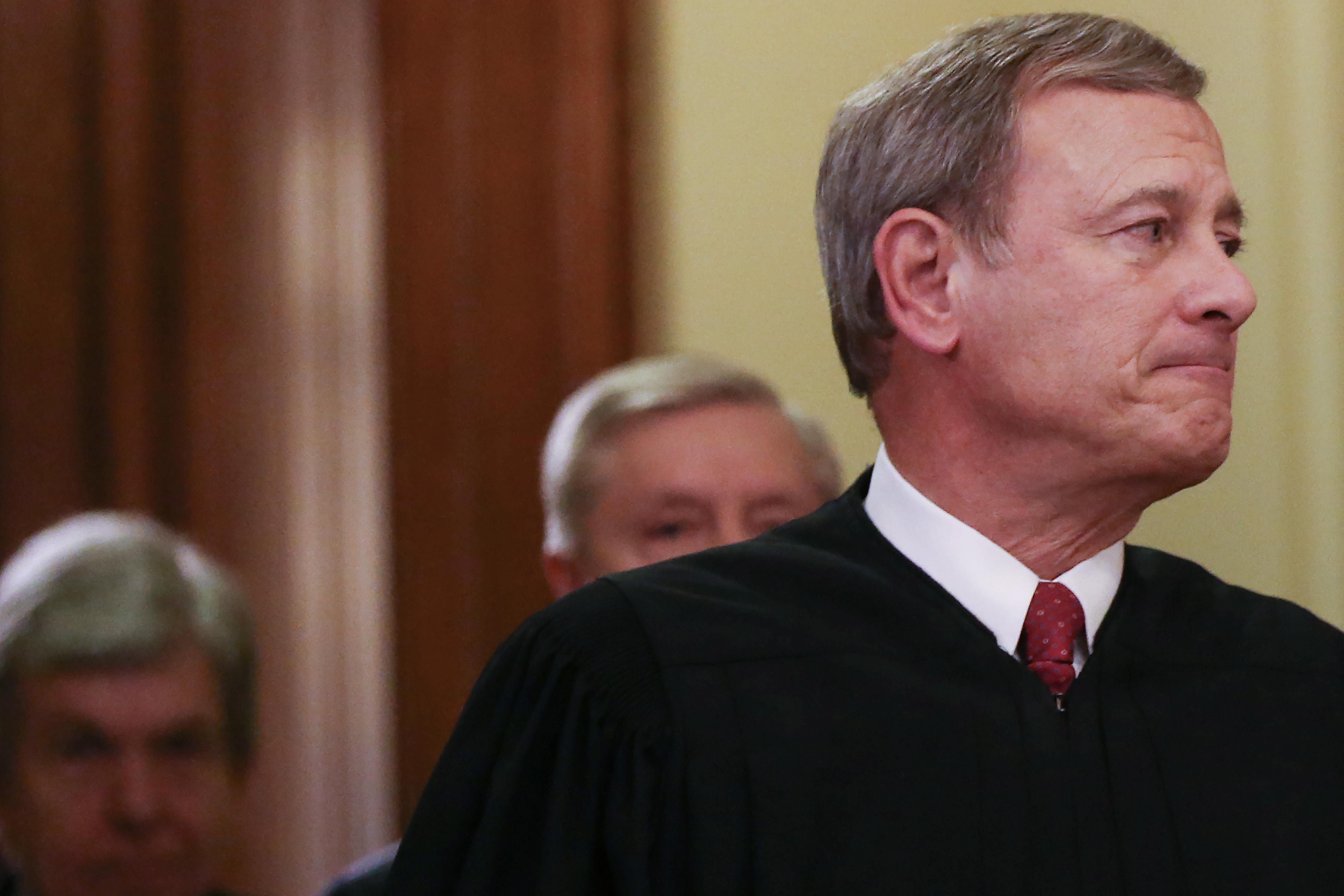

On Thursday, Chief Justice John Roberts joined the liberals to block President Donald Trump’s rescission of DACA, the program protecting Dreamers from deportation. The court’s 5–4 ruling is a resounding humanitarian victory. But Roberts did not save DACA because his heart bleeds for young immigrants who faced banishment to a foreign country. He saved DACA because the Trump administration bungled every step of its attempted repeal, hoping the courts would ignore its sloppy, dishonest corner-cutting. Four conservative justices were happy to do just that. Roberts’ refusal to rubber-stamp Trump’s botched rescission just ensured that more than 700,000 Dreamers can remain in the only country they’ve ever known as home—at least until the Trump administration gets its act together and attempts a do-over.

President Barack Obama enacted DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, in 2012. The program allows individuals brought to the United States illegally as children to indefinitely defer their deportation. DACA beneficiaries also receive a work permit, as well as Social Security and Medicare benefits. Because it’s an executive program, though, DACA’s protections were always tenuous. A president can repeal his predecessor’s executive actions—as long as he follows the rules. And in September 2017, then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Trump administration would begin to wind down DACA, stripping Dreamers of their status as “lawfully present.”

Sessions didn’t know it, but on that day, he laid the groundwork for Thursday’s ruling. The attorney general asked then–acting Secretary of Homeland Security Elaine Duke to rescind DACA because, he claimed, it is illegal. Duke then issued a brief justification for DACA repeal. Her memo explained that the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals had found that a similar but more expansive program, DAPA, was unlawful. (DAPA would’ve protected the undocumented parents of citizens and lawful permanent residents.) “Taking into consideration” the 5th Circuit’s decision alongside Sessions’ own position, Duke wrote, DACA “should be terminated.” The Department of Homeland Security then began winding down the program.

As Roberts explained on Thursday, however, Duke had much more discretion than her memo suggested. According to Sessions, DACA is illegal because it “has the same legal … defects that the courts recognized as to DAPA.” But the 5th Circuit found that only one half of DAPA crossed the line: its extension of government benefits. The court did not say that the other half of DAPA, deferred deportation (or “forbearance”), was illegal. Yet Duke treated both halves as an inseparable whole, never even considering the possibility of ending government benefits for Dreamers while continuing to defer their deportation.

“Removing benefits eligibility while continuing forbearance,” Roberts wrote, “remained squarely within [Duke’s] discretion.” She therefore had an obligation to explain why she rejected this option. By failing to do so, Duke acted in an “arbitrary and capricious” manner in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs these executive actions.

It gets worse. Duke, the chief justice noted, never asked if there was “legitimate reliance” on DACA. When an executive agency “changes course” by changing the rules, it must ask how its new rule will affect people who relied on the old one. Here, the “reliance interests” are powerful: DACA allowed more than 700,000 people to live and work legally in the United States. As Roberts noted, the program’s recipients have “enrolled in degree programs, embarked on careers, started businesses, purchased homes, and even married and had children.” Abruptly revoking Dreamers’ work permits could “result in the loss of $215 billion in economic activity and an associated $60 billion in federal tax revenue over the next ten years.” In light of these consequences, Duke could have “considered more accommodating termination dates for recipients caught in the middle of a time-bounded commitment, to allow them to, say, graduate from their course of study, complete their military service, or finish a medical treatment regimen.”

But Duke did no such thing. She simply ignored the weighty costs to real people and the nation at large. By doing so, Roberts held, she acted in an unlawfully arbitrary and capricious way.

After multiple court losses, the Justice Department figured out that Sessions and Duke’s scheme was legally problematic. That’s why, in 2018, it had Duke’s successor, DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, issue a new memo to shore up the old one. Nielsen provided a slew of retroactive justifications for DACA repeal; she also considered, and rejected, possible reliance interests. Roberts, though, found Nielsen’s memo irrelevant. It is a “foundational principle of administrative law,” the chief justice wrote, that courts can only look at “the grounds that the agency invoked when it took the action.” If Nielsen wanted to elaborate on the legal reasons for DACA repeal, she could only discuss those justifications Duke provided. Nielsen, Roberts determined, broke this rule by throwing in post-hoc rationalizations that are nowhere to be found in Duke’s memo. So the court can only look at the original memo—and that memo’s reasoning is “arbitrary and capricious.”

Roberts’ opinion is strikingly similar to his decision last year blocking the census citizenship question. In each case, the Trump administration cut corners in a mad dash to enact new policy. In each case, it provided dubious, flimsy, and outright dishonest reasons for its actions. In each case, it hoped the Supreme Court’s conservatives would disregard its ineptitude and mendacity and serve as a rubber stamp. And in each case, Roberts refused to play along, drawing a line in the sand. The chief justice is not a closet liberal, but he is a stickler for the rules. And he is not willing to let Trump bend those rules without, at a minimum, a more plausible pretext.

Thursday’s decision is narrow. It allows the Trump administration to attempt a do-over, to start from the beginning and repeal DACA legally. It rejects the plaintiffs’ claim that the administration acted out of racist animus in violation of equal protection. (Only Justice Sonia Sotomayor would’ve preserved those claims.) All four dissenters—Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh—treat the decision as an earthquake and an overreach. But in reality, it is a careful, circumscribed ruling, one that gives Trump the power to end DACA if his administration can figure out how to do it legally. There’s little doubt that, if the president wins a second term, he will rescind DACA the right way, once again putting Dreamers in the crosshairs.

At bottom, Roberts’ opinion is about political accountability. If Trump and his allies want to strip lawful status from Dreamers, the chief justice indicated, they must be clear and candid about their reasons for doing so. The American people deserve to know why an administration would take such a dramatic and damaging step. Trump’s appointees cannot just claim, without persuasive evidence, that they are legally obligated to end DACA. At the end of the day, the president, who is accountable to the voters, must own his decision.