The Trump campaign isn’t subtle. In an ad over the summer titled “Break In,” an older white woman is watching news coverage about activist demands to “defund the police” when she spots a burglar scouting her home’s perimeter and begins to dial 911. As the burglar attempts to force his way in, we hear Sean Hannity’s voice coming from the television, talking about how Joe Biden is “absolutely on board with defunding the police.” Before the woman can alert the authorities, the intruder crowbars his way into the home. He approaches her, and, following an implied assault, the phone falls to the ground.

“You won’t be safe in Joe Biden’s America,” the screen reads.

The ad is a lurid rehash of Trump’s 2016 campaign strategy: using fear of American carnage to mobilize elderly white voters. The political problem that the Trump campaign now faces, though, is that those voters—older, white women, specifically—don’t feel safe in Donald Trump’s America.

In 2016, older voters were one of Trump’s best demographics. According to exit polls, while Hillary Clinton won voters 45 and under by 14 percentage points, Trump won voters 45 and older—the larger age cohort—by 8 points. A separate Pew Research Center study of the electorate found that voters 65 and older were Trump’s strongest overall age demographic last time around. He won them by 9 points.

But while the country has spent four years bracing itself for a replay of November 2016, with eyes fixed on the same Pennsylvania-to-Wisconsin battlegrounds as before, the age-demographic landscape of the presidential contest has been quietly and dramatically rearranged. Although polling in recent months has shown Trump maintaining his advantage among the 50-to-64-year-old cohort, support among those over 65 has moved sharply toward Biden. In a national survey from Monmouth University released on Aug. 11, for example, which gave Biden a 10-point lead overall, Biden was leading registered voters over 65 by 17 points. That would represent a shift of 26 points among the oldest measured demographic from 2016. A Quinnipiac national poll from mid-July, meanwhile, showed Biden’s lead among the 65-plus at 14 points.

Surveys since the two conventions, and the Trump campaign’s blitz to hang urban riots and violence around Democrats’ necks, largely show Biden’s strength among seniors remaining steadfast. A CNN national poll released in early September saw Biden leading among the 65-plus set by 17 points, while a Quinnipiac national poll saw him leading by 4. In some recent state polls where Biden’s margins are tightening, meanwhile, seniors are no longer a bonus demographic contributing to a prospective Biden landslide—they’re the ones responsible for Biden holding onto his lead. An early September Quinnipiac poll of Florida, in which Biden led overall by 3 points, saw him leading among the 65-plus by 10; a Monmouth poll of Pennsylvania, in which Biden led overall by 4, showed him with an 11-point edge among seniors. The Biden campaign spent heavily in swing states over the summer trying to preserve this advantage.

Is this the battle we expected? After the 2016 election, Democrats felt their restoration hinged on rebuilding the Obama coalition, by drastically improving turnout among young people and minorities and mitigating their damage among the white working class. Those improvements are still important. But Biden is creating his own coalition, and some of the most dramatic movement that’s taking place, and some of the aggressively contested terrain down the stretch, is among older white voters in both the Sun Belt and the Midwest. Now, the Biden campaign has the opportunity to do something that Democrats haven’t done since the 2000 campaign: win seniors. If Biden succeeds, it will be a catastrophic blow to the Trump campaign.

“Seniors were a strength group for Trump in 2016. They were a strength group in 2018. Given the challenges we have with other voter groups, we’ve got to work to bring them back into the fold,” Glen Bolger of Public Opinion Strategies, a top Republican pollster and strategist, told me in July. I asked him how optimistic he was about the ability of the Republican incumbent—who, at the time, was embarking on one of his ephemeral pivots to a “new tone”—to do this.

“I don’t have a choice but to be optimistic,” he said. “If we can’t get back to our position of strength with senior citizens, it’s going to be a long election—well, I was going to say ‘night,’ but I guess ‘month’ by the time they’re finally done counting votes.”

Before seniors were a reliable Republican voting bloc, they were a reliable Democratic one.

Al Gore narrowly won the votes of seniors in 2000, but 65-plus voters were one of Bill Clinton’s strongest demographics in his 1992 victory, and he carried them again in his comfortable 1996 reelection. This was in line with older voters’ affiliations of the time: From 1992 until 2010, without interruption, more seniors identified as Democrats than Republicans.

That all changed during Obama’s presidency, as seniors became more likely to identify as Republicans. The switch, as Gallup explained in a 2014 analysis about how seniors had “realigned,” was closely correlated with an overall shift among white voters away from the Democratic Party. With seniors being disproportionately white relative to the national average, the shift in their political alignment was substantial.

Biden’s polling strength with seniors, then, is partly reflective of his overall improvement in standing among white voters compared with Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton. But seniors, along with college-educated, suburban whites, are one of the demographics where that improvement is particularly pronounced.

Biden has tested well among seniors in hypotheticals against Trump since 2015, when he also mulled a presidential bid. And as a Washington Post analysis in May showed, Biden has led Trump among 65-plus voters throughout the election cycle, and performed consistently better among them versus Trump than his nearest primary competitor, Sen. Bernie Sanders, did.

The Post analysis couldn’t divine from the data a verifiable reason that Biden has a higher floor with white seniors against Trump than Clinton or Sanders did. Is it because he’s perceived as more moderate than the others? Because he’s a moderate white man? Because he says things, in the year 2020, like, “Look, the carny show’s gone through town once, and they found out there’s no pea under any of the three shells”?

Jim Farr would say it’s because of the kind of man he is. Farr, 77, retired to Kissimmee, Florida, from Papua New Guinea, where he worked as a Bible translator, a year ago. He’s a conservative Christian who served in the Army, who believes that abortion is murdering babies, and who couldn’t support Hillary Clinton because she wouldn’t accept responsibility for the 2012 Benghazi attack. Farr voted for Trump, even though he behaved like a “3-year-old.” In November, he told me, he will likely vote for Republicans down-ballot—and Joe Biden for president.

“I was hoping that if [Trump] started out at an emotional 3-year-old level, he would now be an adult,” Farr said, “but he seems to have regressed to a 2-year-old.” Even though he doesn’t agree with Biden on either economic or social policy, he comes across as “measured” and trustworthy.

“A bad plan with good people will work,” he said. “A good plan with bad people won’t.”

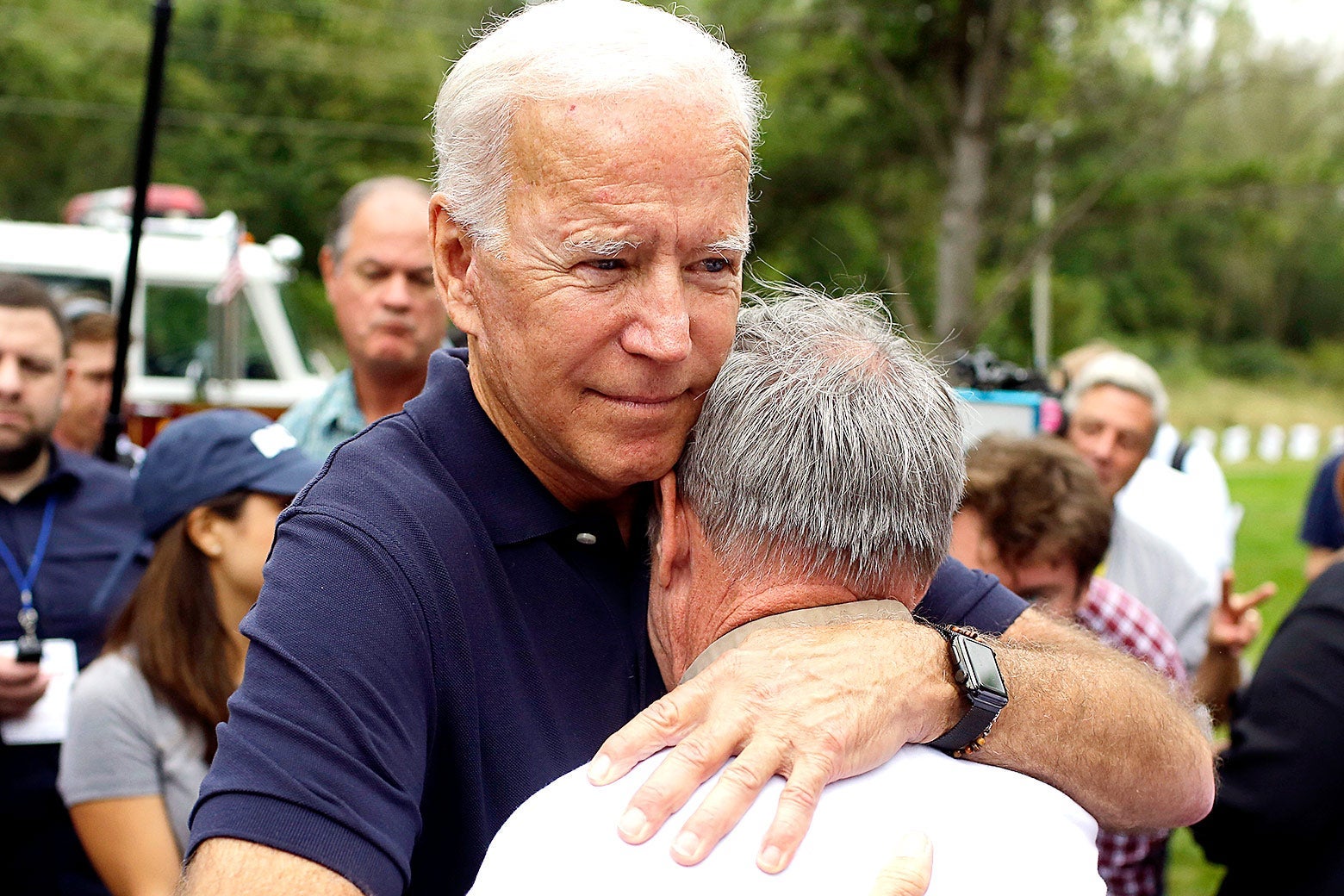

Comparing the character of the two candidates—well, that’s exactly what Democrats want voters to do. “Older voters are the most concerned about the way [Trump] comports himself as president,” Democratic strategist Tad Devine told me. “I think there’s also a comfort factor with Biden that perhaps they didn’t have with Clinton as much. He’s someone that they know, and I think they’re very comfortable with him, the way he comports himself, the kind of person he is.”

Seniors also have a small-c conservative way of not wanting to see things get too disrupted. “Trump really has worn out his welcome with these people,” Devine added. “I think many of them voted for Trump because they wanted to maybe put a brake on the change that they were seeing happening in the country in such a short amount of time. Now I think they want to put a brake on Trump.”

There’s also a specific issue that’s been in the news of late that’s of particular concern to seniors.

Helen Lyon, 73, of Grand Junction, Colorado, has been a Republican since 1972. She held her nose and voted for Trump in 2016, with the encouragement of friends who told her Trump was a good businessman who could shake things up.

She told me she felt she was living in a state of “cognitive dissonance” for much of Trump’s presidency. Her husband, a Democrat, “loves to watch Colbert,” whom she found irritating.

“I would kind of get ticked off,” she said, “because he was making fun of my president.”

After a while, though, she found that she kept asking her husband, “Did [Trump] really say that? Did he really tweet that? Did he really do that?” She would then look up what Trump said, tweeted, or did, and she began to wonder if she could vote for him again.

“And then, when COVID came,” she said, “and the way that he handled it and just said it was going to go away, I guess that was finally the minute that I was able to step out of that cognitive dissonance and say, ‘I cannot—I cannot—vote for this man.’ ”

It is not high-level political analysis to determine that the global plague disproportionately affecting older people, which has killed nearly 200,000 Americans in the last six months, has weakened the incumbent’s position among seniors. Even though Biden had maintained a higher-than-usual floor among seniors in a matchup against Trump, his strength increased noticeably as the coronavirus outbreak dragged into late spring.

John Hishta, the senior vice president for campaigns at AARP, insisted to me that the core issues for seniors in this election haven’t changed. It’s that the pandemic has heightened their concern around those issues.

“Ultimately, at the end of the day, the core issues of Social Security, Medicare, health care, and things like prescription drugs still are the most important issues for older voters,” Hishta told me. “They just are. And I don’t think that’s changed in all the years I’ve been doing this stuff. Certainly it hasn’t changed in the 10 years I’ve been with AARP.”

The pandemic, in Hishta’s view, has just “exacerbated people’s uneasiness and feelings about their own health and well-being.” And Trump’s response to the pandemic has done the same.

It may seem like a distant memory now, but there was a time—two or three “new tones” ago—that Trump’s job approval actually improved during the coronavirus outbreak. After months of ignoring the threat the virus posed, Trump adopted his first “newfound somber tone” in mid-March and began holding lengthy, daily press briefings alongside public health experts and the rest of his coronavirus task force. By the end of March, his approval ratings had measurably improved. Whether he was providing leadership is one question. But at least he was on television pantomiming the image of a leader taking a problem seriously.

But soon the artifice collapsed. Cases and deaths continued to pile up, and the daily opportunity to address the public on task force developments devolved into an opportunity to speculate about the efficacy of injecting household cleaning products. Trump stopped talking with Dr. Anthony Fauci and started emphasizing the need to rapidly reopen the economy. (There was a calamitous handling of race relations and treatment of protesters that tanked his numbers in the middle of this too.) With both his head-to-head numbers against Biden and approval of his handling of the virus in free-fall, we were back to the beginning: Another new, somber tone, and a resumption of daily press briefings in late July, to perform the motions of being on top of an issue that was killing him with a demographic he needed. But then, in his first press briefing back, the president wished Ghislaine Maxwell, the accused sex trafficker and accomplice to Jeffrey Epstein, well.

It was a few days after this that I spoke to Terry Sullivan, a Republican strategist who managed Sen. Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign in 2016. He did not think resuming the press briefings was a smart strategy.

“If you think that him talking more about putting sunshine and bleach inside the body was helpful to him with seniors?” Sullivan said. “Well, good on you, but that’s not necessarily borne out in the data I’ve seen.”

Perhaps there’s only a certain amount of damage from which public relations yo-yoing can distract when the stakes reach a certain level. For seniors, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The coronavirus epidemic is a daily reminder of their mortality. Trump being crude, provocative, and inexperienced was tolerable for some (mostly white) older voters when it was at a distance, and the economy was humming. Trump’s style, in which mayhem is the message, now represents an immediate danger.

Lori McCammon, 65, of Alma, Wisconsin, voted for Trump in the last election, when she was living in Southern California. She now says Trump is guilty of “voluntary manslaughter” for those who have died from COVID-19.

In 2016, McCammon had been concerned about illegal immigration from Mexico. She also didn’t like Hillary Clinton.

“I don’t have a reason, I don’t know,” she told me. “I just didn’t like her.”

She says she almost instantly regretted her vote, and can’t bear to watch Trump speak anymore.

“I consider myself very lucky so far that someone close to me hasn’t contracted or died from it,” she said of the coronavirus. “My immediate family is all gone from various illnesses. I haven’t lost anybody to COVID, but I’ve lost my family. So I feel the pain of losing a parent or losing a sibling.”

McCammon told me that she isn’t sure she’ll ever vote for another Republican again.

In the November 2019 Democratic presidential debate, Sen. Kamala Harris, in what turned out to be a last stand for her campaign, repeatedly argued that she was the candidate most capable of reconstructing the “Obama coalition” that had as its backbone wide margins and high turnout from young people, Hispanic voters, and Black voters. Biden, hearing the word Obama, claimed that he would be better suited for the task because he’s “part of the Obama coalition.” He would add, in one of his more curiously worded debate lines of the cycle, that “I come out of the Black community, in terms of his support.”

The two now share a ticket that’s favored—though we would like to emphasize here, not certain—to win the general election. But they won’t do it through a simple reconstruction of the Obama coalition.

As it looks today, Biden will, like Obama, win young voters, Black voters, and Hispanic voters by wide margins, though not necessarily as wide. But unlike Obama, who twice lost white voters with college degrees, Biden is leading with that group by upward of 20 percentage points. Meanwhile, 65-plus voters were Obama’s worst age demographic in both 2008 and 2012. There’s now a chance that Biden could win them.

Even if Biden slips and doesn’t outright win seniors—mean reversion as we approach Election Day is always a fair bet—a significant shift of 65-plussers away from Trump could have a profound effect on the outcome of the election. For one, seniors always have the highest turnout rate in elections, a fail-safe that could offset the Biden campaign’s issues with enthusiasm among younger voters. Looking at the polls, as Terry Sullivan put it, “a point or two amongst older voters is worth three or four or five with younger voters.”

And there’s something else: Critical swing states like Arizona, Florida, Michigan, and Pennsylvania all have disproportionately higher shares of the senior electorate. For 2020, an early Pew look at the national breakdown estimated that the 65-or-older cohort would be 23 percent. According to an analysis performed by the firm Echelon Insights that AARP commissioned, 25 percent of Pennsylvania’s electorate, 25.9 percent of Michigan’s, 29.6 percent of Arizona’s, and 30.5 percent of Florida’s were over 65 years old in 2016. It’s that particularly high rate of seniors in Florida that makes even Biden’s slim lead in the state such a blinking red light for the Trump campaign.

The story of 2016 was how the “blue wall” collapsed as Clinton narrowly fell to Trump in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. For three years, then, the dominant narrative has been about how Democrats needed to reconstruct the same “blue wall” by either flipping roughly 70,000 white, working-class diner patrons spread across those three states or turning out 70,000 likely Democratic voters who stayed home. This, and this alone, is what the election would be.

This way of thinking misses what is, frankly, one of the only interesting things about presidential elections: the entrepreneurial way that nominees build coalitions tailored to them and, in doing so, change American politics. After John Kerry lost in 2004, some Democrats thought they needed to nominate a folksy white guy from the South. Instead they nominated Illinois’ Barack Obama and won in a landslide with a coalition of Obama’s making. After Mitt Romney lost in 2012, the Republican National Committee wrote an “autopsy” pleading with its leaders to soften their stance on issues like immigration. Instead, the party nominated Donald Trump and won the general election. Hillary Clinton’s defeat was blamed, among leftists and populists, on her being an establishment candidate tied to the dispiriting memories of ’90s centrism. Now the Democrats are holding a steady lead with another establishment-endorsed ’90s holdover, as old white voters rally to a figure from the old days.

That the 2020 campaigns would be focused on the votes of white senior citizens in Florida as a key determinant of the election—an election whose integrity hinges on adequate funding of the United States Postal Service during a global health crisis—is not what many of us would have anticipated a couple of years ago. But it never is.