Six years ago, Karin Leuthy, a registered Democrat, voted for Republican Sen. Susan Collins. Like many Mainers, Leuthy, 48, took pride in not voting a straight party ticket that year. “I thought it was really important to have women in the Senate who were Republican, who were pro-choice, who would protect reproductive rights and be a check to the men in the Republican Party,” Leuthy said.

Leuthy lives in Camden, a coastal town with a picturesque harbor and a ski area that hosts a national toboggan championship every year. Her daughter raises sheep, which they board at a nearby farm. In 2014, when she last voted for Collins, Leuthy was an avid news consumer and regular voter, but not an activist. She admired Olympia Snowe, Maine’s long-serving Republican senator who retired in 2012 out of frustration with Senate partisanship. “Snowe was very thoughtful. She was straightforward. And she had a way of working in a diplomatic fashion that I think a lot of Mainers really appreciated,” Leuthy said. “I thought Susan Collins was going to serve in an Olympia Snowe model. I was very wrong. Very wrong.”

Ask a handful of Maine Democrats for their thoughts on Collins’ current reelection campaign, and you’re likely to hear at least a few stories that mirror Leuthy’s. At a late-February bean supper in Skowhegan hosted by Sara Gideon, the speaker of the Maine House of Representatives and now Collins’ Democratic challenger, I talked to more than a dozen attendees. Some lived in the 8,500-person town in central Maine; others had traveled to the steelworkers’ union hall from up to an hour away. They were mostly registered Democrats—some committed to Gideon, some still considering her primary opponents. Almost all of them had voted for Collins in previous elections. None planned to do so again.

In 2014, Collins won her fourth term with more than 68 percent of the vote. She won every county, every age group, every education level, every income bracket, and nearly 40 percent of Democratic voters. The next year, with a 78 percent approval rating in the state, Collins was ranked the most popular Republican senator. Back then, she enjoyed a reputation among many of her Democratic constituents as a prudent, upstanding moderate, a perception shored up by her occasional consequential swing votes that swung toward the Democrats. A regular stream of analyses named her the “most bipartisan” and “most disagreeable”—as in party-bucking—member of the Senate.

That picture of Collins, who was also named the Republican senator most likely to back Barack Obama’s positions, hasn’t always told the full story. The tallies that led to those titles include votes made only for procedural reasons and votes to pass Cabinet or judicial nominations, which Collins almost always supports, regardless of the president’s party affiliation. The bills she co-sponsors with Democrats—the ones that make her the “most bipartisan”—rarely make it to a vote. They often concern important but not particularly far-reaching or controversial issues: helping states build out broadband networks or reauthorizing a geriatric care workforce development program. Many peter out in committee, making them far more consequential to the co-sponsors’ respective bipartisan rankings than to the American people.

In the more consequential votes, Collins’ record has been mixed. She memorably cast a decisive vote against the GOP’s attempted repeal of the Affordable Care Act in 2017—but a few months later, she voted for the GOP tax bill that repealed the individual mandate. Collins opposed Betsy DeVos for secretary of education but only after casting an essential vote to send her nomination out of committee and onto the Senate floor. Collins made an eloquent defense of Planned Parenthood with her 2017 vote against the ACA repeal, then gave an equally impassioned speech in favor of Brett Kavanaugh, who’d go on to set the stage for a possible future rollback of abortion rights in his June Medical Services v. Gee dissent. She was one of just two Senate Republicans to vote in favor of allowing witnesses in Donald Trump’s impeachment trial but ultimately voted to acquit him, saying that Trump had learned an important lesson and would be “much more cautious in the future.” These actions have taken a toll: In January, Collins clocked in as the most unpopular senator, period.

Her bid for reelection, a foregone conclusion in previous years, is now a tight race. Since getting the nomination, Gideon has beaten Collins in every major poll, with independents and undecideds both leaning her way. Collins still has a chance to win—she’s the incumbent, and Gideon’s lead is not that large—but she’s going to have to fight for it. And the stakes are high: Collins’ seat is a linchpin of the Democratic Party’s plan to retake the Senate. Democrats need to win four Senate seats to gain a majority—three if Joe Biden wins the presidency—and Collins holds one of the seven Republican seats that look flippable. Only Sen. Martha McSally of Arizona is rated more vulnerable, according to the Cook Political Report.

That vulnerability points to something else happening in Maine, something that polling data can’t quite capture. In the years since Collins’ last reelection, Donald Trump’s presidency and the new left-leaning activist infrastructure that has sprung up in response to it have changed the state’s political landscape. Many Maine independents and Democrats told me they felt they’d been awakened from a period of political complacency—able to see clearly, for the first time, that Collins wasn’t the moderating force in the Senate she claimed to be. People like Leuthy, who had voted for Collins in the past, are now actively organizing against her.

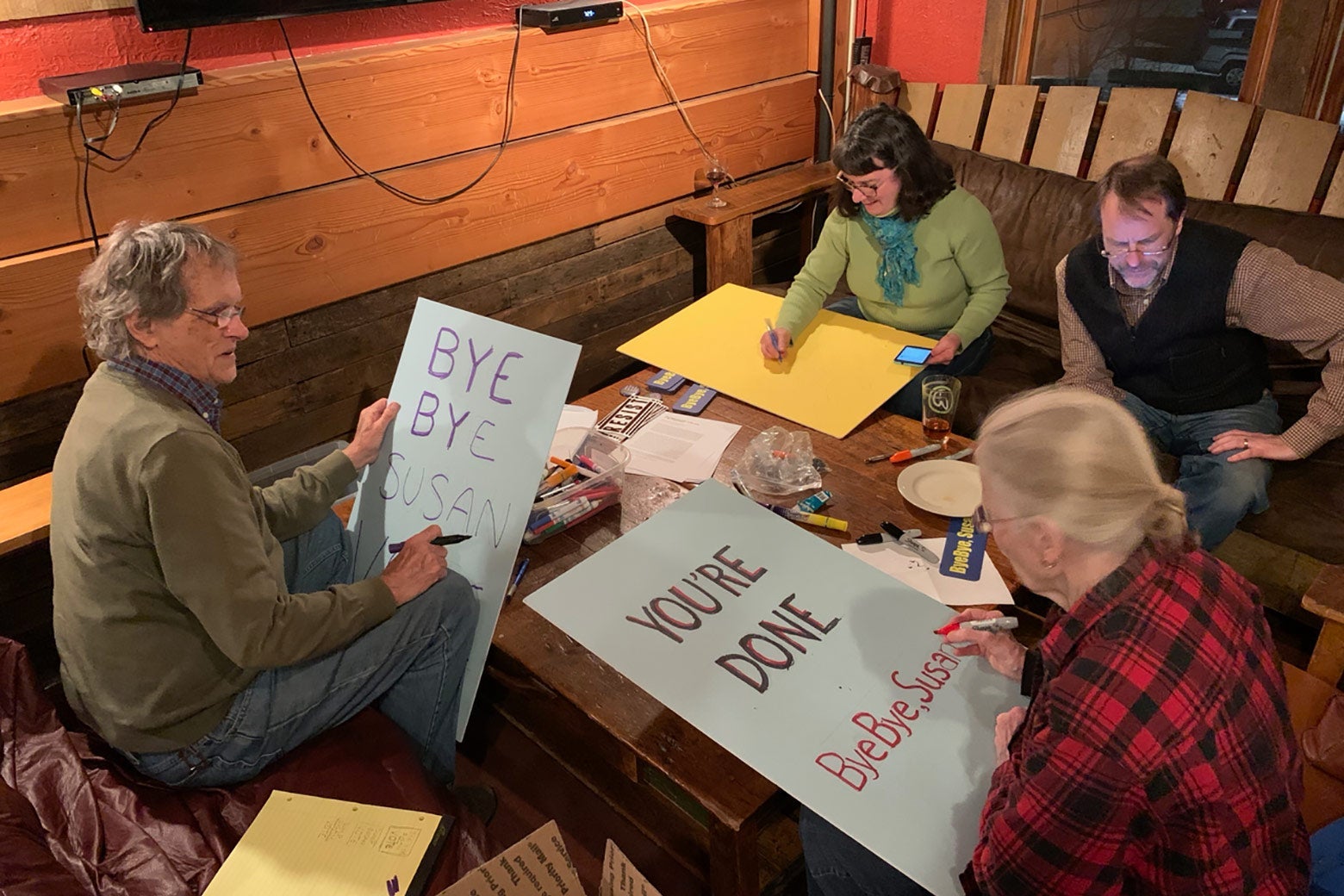

Shocked and dismayed in the weeks after Trump’s election, Leuthy formed a Facebook group of other equally dismayed Mainers and began posting calls to action. Over the course of several months, she turned the group into a volunteer-run organization called Suit Up Maine, which produces explainers, legislation guides, and talking points for voters and activists around the state. Leuthy says the group is “aggressively progressive” but avowedly nonpartisan—an important distinction in a state with an active Green Independent Party and an electorate that can be “quite distrustful of political parties.” Trump may have prompted Suit Up Maine’s formation, but he’s not its only target. “Susan Collins and Trump are sharing the top of the list right now,” Leuthy said. In just under three years, Leuthy has transformed from a person who’d look at political lawn signs and think, “Why can’t people keep their opinions to themselves?” to one who bought a foot-long drill bit to penetrate Maine’s frozen earth so she could place lawn signs around town last winter.

The story of Democratic voters becoming newly politically active in the wake of Trump’s election is familiar, and it’s played out, to some extent, in every state. But Collins isn’t every state’s Republican senator. She’s one of very few federal legislators who was previously seen as a reasonable leader—and, crucially, a potentially convincible ally—by a sizable number of her opposing-party constituents. Many voters I spoke with extolled Maine’s tradition of sending independent-minded, plain-spoken legislators to Washington, and for years, Collins reaped the rewards of that proclivity. But now, everything’s changed. In 2018, Democrats made their partisan presence known in the state, flipping the governorship from red to blue by electing Democrat Janet Mills, flipping their state Senate, and replacing an incumbent Republican congressman with Democratic Rep. Jared Golden in a district Trump won by 10 points.* For liberals in Maine, those midterm election results were the first bit of evidence that all their anger could have tangible results. This fall, the Collins race will be the second opportunity for Maine to show what’s changed. “We’re very small potatoes in terms of the national election. We don’t have that many delegates,” Sarah Holland, 60, a former Collins supporter, told me of Maine’s limited impact on the presidential race. “But Susan Collins is our responsibility. I feel like that’s on our shoulders as Mainers to take care of that.”

If you want to know how much Trump’s election changed Maine politics, start with the Maine Democratic Party. Its chair, Kathleen Marra, had never been involved in party politics or political organizing before 2017. “All I ever did was vote,” she told me. Stricken by Trump’s win, she attended the first Women’s March in D.C. and became involved in local left-leaning activist groups. In December 2017, she led a march held in the middle of a snowstorm to protest Collins’ decisive vote in favor of the Republican tax cuts. Despite the weather, it was a dramatic, well-attended event. Before she was elected to her current position in 2019, Marra grew the Democratic Committee in her 10,000-person hometown of Kittery from a club of eight people who gathered to caucus every two years to 180 members, a few dozen of whom now meet every month.

Marra says she’s seen Kittery-like growth in Democratic activities all across the state. In 2019, the party signed up twice as many volunteers as it did in 2017, the last non-election year. And then there are all the groups. In addition to Suit Up Maine and the 15 Indivisible chapters in the state, there’s Mainers for Accountable Leadership, which grew out of a Pantsuit Nation Maine Facebook post and now trains activists to bird-dog public officials; Moral Movement Maine, whose members locked themselves in Collins’ Portland office to protest her vote on the 2017 tax bill; and Resist Central Maine, whose members visited Republican Rep. Bruce Poliquin’s office twice a week, every week, before he was ousted in 2018. In 2018, the Democratic turnout rate matched the Republicans’ for the first time in years: 42,000 more Democrats voted than Republicans in the state (registered Democrats have long outnumbered registered Republicans in Maine; the latter just used to turn out for elections in higher rates).

This is all very heartening to Shenna Bellows, the Democrat who lost to Collins in 2014. Back then, Bellows’ strategy was to debunk the myth of a moderate Susan Collins, but it was nearly impossible. In early polling and message testing, the Bellows campaign found that Mainers didn’t think Collins had ever cast a vote that obstructed reproductive rights or environmental protections. “Even when presented with various specific factual examples, most voters didn’t believe that that was true,” Bellows told me. Her uphill battle was steepened by a total lack of institutional support from the Democratic Party and other ideologically compatible organizations. The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee thought Collins was invincible after she beat her previous Democratic challenger, former Rep. Tom Allen, by 23 points in 2008. The DSCC didn’t even recruit a challenger in 2014, and it didn’t give Bellows a single dollar once it endorsed her when she entered the race. Planned Parenthood essentially sat the 2014 race out, announcing that both Bellows and Collins had strong records on reproductive rights. It endorsed neither candidate and gave no money, then admonished Bellows in the press when she accurately noted that Collins had voted for an appropriations bill that would have defunded Planned Parenthood. Without the wholehearted financial and grassroots support of the people who should have been her allies, Bellows’ campaign struggled. “We didn’t even get to 50 percent name recognition until August of 2014,” she said.

Bellows says Democratic voters in Maine have traditionally spent their energies on issue-based movements like civil rights, environmental protections, and reproductive rights. In 2014, Collins campaigned on what she said was a strong record in those areas, and she had endorsements from the likes of the League of Conservation Voters and the Human Rights Campaign to back her up. (That latter endorsement stung for Bellows, who had served on the executive committee of Maine Freedom to Marry for seven years, while Collins had refused to support equal marriage rights.) But since 2016, Democrats have been more willing to organize around partisan politics, Bellows, who now serves in the state Senate, told me. And Collins helped them get there.

In the midst of her despair as Trump was being inaugurated, Linda Mosley, 59, remembers thinking, “Well, at least we have Sen. Collins.” When Collins cast a crucial vote to protect the Affordable Care Act in 2017, Leuthy visited Collins’ Augusta office to deliver thank-you notes; one Indivisible chapter made graphics depicting the senator as Wonder Woman and Rosie the Riveter. But eventually it became clear that Collins, who had written an op-ed criticizing Trump before the election, was not going to be the bulwark against Trump so many of these voters hoped she’d be. “This was [Collins’] chance to not worry about keeping her job, but just do the right thing. And she did not do it,” Bill Charity, 63, told me at the bean supper.

Ask a former Collins voter why he turned against her, and you might get any number of responses: her vote to acquit Trump at the end of his impeachment trial, her pro-Kavanaugh speech, her vote for a tax bill that served corporations and the wealthy. But hovering over all of this is a simple disappointment that Susan Collins just didn’t turn out to be who they thought she was. “I thought she supported women’s rights because she always said she did,” Holland told me. “I thought she supported the environment. And now, she has just failed every one of those tests. I don’t know what happened to her.”

Doug Poulin, 74, joined the Indivisible chapter in Bangor after Trump’s election, which he calls “a get-off-my-butt experience.” Every action the group has taken has been a first for Poulin. “I had never marched, I had never phone-banked, I had never canvassed,” he told me. Over the past three years, Poulin’s done all these things, plus dress up as a handmaid at one of the hundreds of street protests the group has organized. He’s also part of an Indivisible Bangor subgroup that meets with Collins’ staff at her Bangor office at least twice a month, which means he’s tried to pin down the legislator’s positions on upcoming votes. It’s completely changed his impression of the senator, who has never agreed to meet with them. “I thought she was more responsive to her constituents—until I had to go and try to get a response from her,” Poulin said.

I heard versions of this story from more than a dozen new activists in Maine. The more they paid attention to how Collins conducted herself in the Senate, and the more invested they felt in their own attempts to get her to thwart Trump’s agenda, the worse she seemed. They tried to show up at her town halls only to find that Collins hasn’t hosted one in two decades. (Slate reached out to Collins’ office to ask about her constituents’ complaints, but did not hear back by press time.) As they gathered in living rooms and pizza parlors and community centers on 6-degree nights, they started hearing their senator dismiss their efforts as the scheming of “paid activists.” “That was one that shocked me,” said Michael Corlew, a member of Indivisible Bangor. “We have no funding. We pay $15 rent for this room by passing around a jar, and we all throw in a couple of dollars.”

Mainers for Accountable Leadership co-founder Marie Follayttar, 44, recalls many hours spent learning the ins and outs of the U.S. Senate alongside her fellow new activists on Facebook in the months after Trump’s inauguration. Hardly anyone knew the difference between a committee vote and a floor vote, for instance—a distinction that became clearer when Collins cast the tie-breaking vote in committee to submit DeVos’ nomination to the full Senate, then voted against DeVos on the floor. People who might have only paid attention to the latter vote during previous presidential administrations were now attuned to, and incensed by, the former.

Suddenly, a whole lot of behind-the-scenes GOP deal-making—the kind that allowed Collins to vote with Democrats and maintain her bipartisan image as long as Republicans had enough votes to win without her—came into focus for many Collins supporters, making the senator look less like a discerning moderate who voted her conscience and more like the kind of partisan operative Mainers distrust. “These were the growing pains of the resistance,” Follayttar said. “Those moments were political awakenings.”

The voters I talked to differed in their opinions on whether it was Collins, the U.S. political landscape, or their own minds that have changed in recent years. But it’s clear that the Trump administration has drawn a bright line for them between right and wrong. It’s not that they think it would have been easy for Collins to stand as a Republican against Trump. Her intermittent votes outside party lines—the main reason she’s kept her seat—look treasonous to the right. As Rebecca Traister wrote in New York magazine, Collins has found herself “torn between an unrelentingly disciplined caucus, Trump’s punitive base, and a liberalish Maine constituency.” But the time in which the ideological and temperamental differences between Collins and Trump might have mattered has passed for Maine Democrats. The two are now inextricably tied. Twice I asked the activists I met if they knew people who still support Collins. Both times they responded with stories about people who support Trump.

These days, nothing enrages post-awakening Mainers more than the idea that Collins is a moderate. Since 2016, Follayttar has led her group in “debunking” Collins—convincing supporters that she’s not the judicious, independent-minded legislator she’s assumed to be. Ditto Leuthy and Suit Up Maine, whose website features a “case against Collins” page that lists “14 Reasons Why Susan Collins Is Not a Moderate.” They appear to be pretty convincing. Rick Parker, a Democrat who’s voted for Collins in previous years, told me that as a former paper mill worker, he’d felt a kinship with Collins, whose family ran a lumber company for generations. “I just thought of her as being like one of us,” he said. Now how does he see her? “She’s a Mitch McConnell righthand man.”

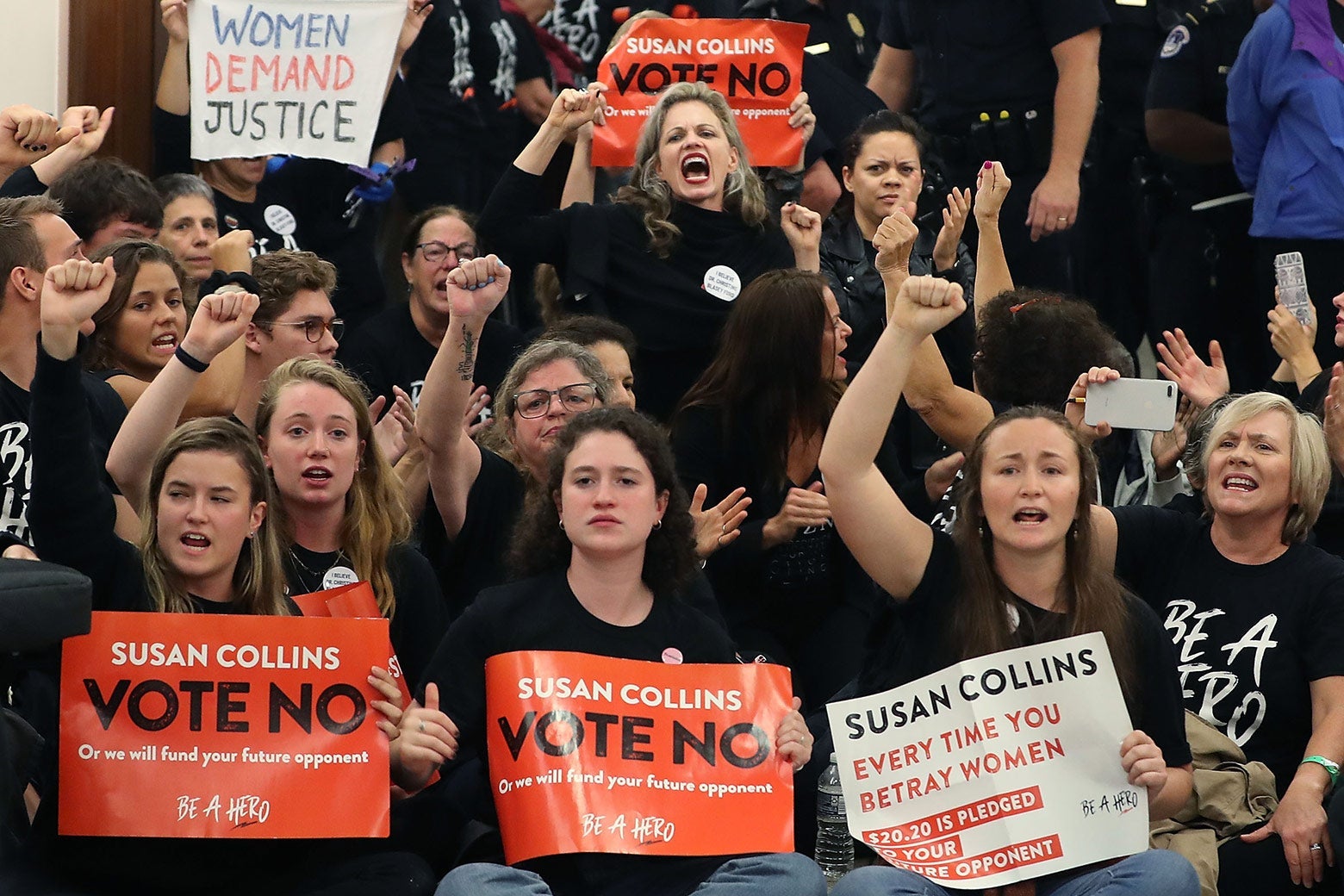

Trump’s election was not the only, or even the most decisive, turning point for Collins. More than anything else, the Kavanaugh confirmation sparked a nationwide campaign against Collins, raising more than $4 million for her eventual opponent, Gideon, and directly tying her Kavanaugh vote to her reelection campaign in American minds. Now, Collins is forced to answer for every decision Kavanaugh makes. This summer, when he issued his dissent on June Medical in support of states trying to curb abortion access, Planned Parenthood issued a press release noting that Collins’ “deciding vote … brought the Supreme Court within one vote of putting safe, legal abortion out of reach for millions.” When reporters asked Collins whether she regretted confirming the justice, who she’d insisted would uphold Roe v. Wade, she issued a statement accusing them of reading the dissent too broadly.

In Maine, the Kavanaugh vote inspired an even sharper and more personal reaction. Weeks before Christine Blasey Ford made her sexual assault allegation, Suit Up Maine teamed up with other advocacy groups to compile a brief on the judge for Collins. Karin Leuthy researched Kavanaugh’s case history, read his opinions, and used Collins’ own professed criteria for Supreme Court justices to make the case that Kavanaugh was a bad choice. “In our mind, we had done everything in the way a senator would want their constituents to interact with them,” Leuthy said. “We were thoughtful. We arranged a meeting. Everything was incredibly wonky and nerdy—no hyperbole in there at all.” According to Leuthy, a Maine-based Collins staffer who met with the group in Augusta for several hours called their briefing packet the most comprehensive constituent-produced document he’d ever seen and promised to include it in the materials Collins would study before meeting with Kavanaugh. The group returned to Augusta to spend more than an hour with another Collins staffer, legislative assistant Katie Brown, when she was in town from D.C.

Things got more heated in Maine once Ford’s story came out. Across the state, her allegation spurred a barrage of personal memories and stories: In local newspaper articles and letters to the editor, in community meetings, and in conversations among friends and neighbors, women exhumed their own experiences with sexual violence. Hundreds of Maine women bought bus tickets and carpooled to D.C. to beg their senator to keep Kavanaugh off the court. Rebecca Millett, a Democrat who represents Cumberland County in the Maine state Senate, joined a convoy of female elected officials from the state—including mayors, city councilors, and state representatives, some of whom shared personal stories of sexual assault—to plead their case to a Collins staffer in Washington.

The Kavanaugh fight was a first major attempt at political advocacy for Melissa Berky. Berky, 65, told me Trump’s election moved her to “put a big lantern on [Collins] to see who she really is, how she really votes.” Her investigation proved disappointing (“she doesn’t stand up well in the light”), but she still believed Collins might be moved by the scores of Mainers knocking down her door about Kavanaugh. “If you didn’t think there was a chance, you could go home and eat ice cream or something,” she said. “But you think there’s a chance, so you have to be out there. It was almost like people were down on their hands and knees literally begging for her vote.” Only a few of the hundreds of Mainers who traveled to D.C. ever managed to get an audience with Collins herself.

Mainers were already upset with how little face time Collins gave her constituents—and then, in her speech announcing her vote to confirm Kavanaugh, the senator scolded them for trying to make their voices heard, bemoaning the “dark money” and “special interest groups” that had “whip[ped] their followers into a frenzy by spreading misrepresentations and outright falsehoods.” She called the protests against Kavanaugh “a caricature of a gutter-level political campaign.” Earlier, she had called fundraising on behalf of her eventual opponent an attempt to “bribe” her.

“It was so offensive,” Leuthy said. “She just threw a blanket over all of us that opposed the Kavanaugh confirmation and called us all an angry mob.” After two weeks of nonstop protests in Bangor, Berky watched Collins’ Kavanaugh speech outside the senator’s local office, which sits in a building named for Mainer Margaret Chase Smith, a long-serving Republican congresswoman and senator who delivered a famous 1950 speech decrying McCarthyism and the bigotry of her own party. “Our faces fell and tears came into our eyes,” Berky recalled. “And I felt like somebody had just taken a knife and stuck it into the women and dug it in.” Leuthy compares Collins’ Kavanaugh speech to the John F. Kennedy assassination: Everyone she knows remembers where they were when they watched it.

When Millett, the state senator, shared her own memory of that speech with me, she had to take a moment to compose herself. “My blood is boiling right now,” she said. It wasn’t just Collins’ decision that enraged the activists who’d pushed her to reject Kavanaugh’s nomination, Millett said. It was the fact that her speech made it sound like she’d made up her mind weeks earlier, then let thousands of women exhaust themselves in protest and bare their painful pasts for nothing. “One of our things we like to say is that women will never forget,” Berky said. “Women will never forget that vote and that betrayal.”

“I actually had this grain of hope that [Collins] would see all this information and hear all of this evidence and weigh all of these facts and come to the logical conclusion,” Leuthy said of the research she had compiled for the senator. “And when she didn’t, I felt really duped, and ashamed that I had been duped. Since then, I am no longer naïve, and I won’t be duped again.”

Since the Kavanaugh vote, Collins has become a reliable love-to-hate target for her detractors, a legislator who needs no further debunking. “We’re done debating whether Susan Collins could represent us well and are just moving to replace her,” said James Cook, 49, of Midcoast Maine Indivisible, which has been holding a weekly “pop-up election info depot” at a busy intersection in Rockland. Even the Lincoln Project, a PAC created by never-Trump Republicans—Collins’ bread and butter!—recently released an ad calling the senator a “fraud” and a “Trump stooge.” And the events of the summer have not worked in her favor: Maine farmers lost thousands of dollars on chicks that arrived dead in the mail, possibly due to Trump’s interference with the U.S. Postal Service. Collins gently condemned Trump’s efforts to defund the USPS and asked the postmaster general to “promptly address” delays in mail delivery, but Democrats pointed out that she sponsored the 2006 bill that caused the agency’s financial troubles in the first place.

Sara Gideon, meanwhile, is reaping all the benefits of her opponent’s fall from favor. Planned Parenthood, which in 2017 bestowed Collins with its Barry Goldwater Award, calling her a “champion for women’s health,” is sending out frequent email blasts denouncing Collins, saying she’s “left Maine behind and is no longer the leader she once was.” The organization endorsed Gideon in January and plans to spend $1.7 million getting her elected. With the $4 million Gideon got from the Kavanaugh-related crowdfunding campaign when she won her primary, she’s far outpacing her opponent on the fundraising front. Last month, the Senate Democrats’ super PAC spent six figures on an ad essentially reminding voters that she’s never killed any mail-order chicks.

In some ways, Gideon’s campaign seems well-suited to the former Collins voter who now associates the senator with a beyond-the-pale president. “Susan Collins has been in the Senate for 22 years,” Gideon said in her campaign announcement video. “At one point, maybe she was different from some of the other folks in Washington. But she doesn’t seem that way anymore.” It’s a message she’s repeated over and over again: A recent ad features a Mainer in a combat veteran’s hat saying, “I believe Susan Collins used to represent Maine in a good way, but she does not anymore.”

Though much of the enthusiasm behind her campaign is coming from furious anti-Trumpers and the newly politically awakened, Gideon is not running on an activist platform. She presents herself as a genuine moderate: She voted for Joe Biden in the Democratic presidential primary, supports a “Medicare for all who want it” national health care policy, and talks more about bipartisan governance than broad systemic change. The sexual assault allegation against Kavanaugh and the threat he poses to reproductive rights might be animating for activists in Maine, but Gideon told me she doesn’t talk much about the Kavanaugh vote on the campaign trail. She believes Mainers—presumably, the ones whose votes she needs to flip—care more about issues that feel closer to home. While the Trump era has been a formative political moment for some former Collins voters, Gideon is targeting those who don’t feel their politics have changed at all. When she told me why she’d urged Collins in a letter to reject Kavanaugh’s nomination, she mentioned only his “temperament.” For whatever it’s worth, that’s the same ideologically neutral problem Collins said she had with Trump in her 2016 op-ed.

Some voters I spoke to were miffed that national advocacy groups endorsed and funded Gideon before Democratic primary voters had a chance to weigh in. “The biggest criticism I’ve heard about Sara Gideon is that she won’t say the words, ‘Medicare for All,’ ” Berky said. “If she is elected, I expect that our group will want to bump her to the left wherever possible.” Others were hopeful that Gideon’s record of pushing past former Republican Gov. Paul “Trump before Trump was popular” LePage on Medicaid expansion and Narcan access was an indication of how she’d stand up to Trump where Collins hasn’t. “She has the backbone and the courage that Susan Collins has lost,” Cook said. Most were just seething mad, well past ready to be rid of a senator who has failed to step up at this tipping point in American democracy, raring to vote for whomever her challenger happened to be.

When I talked to Shenna Bellows, Collins’ last challenger who couldn’t break through, she told me that she sees some similarities between this year’s Senate election and a major campaign in her past: not her race against Collins, but her push for marriage equality in Maine. In 2009, in a statewide referendum, voters rejected same-sex marriage. Three years later, they approved it. In the intervening years, Bellows said, the Freedom to Marry campaign focused on “creating permission for people to change their minds.” There was no shaming, no trying to convince people in 2012 that they’d made a bad choice in 2009. Just a message that it was time for a different outcome. If Gideon wins in November, she and her allies will have persuaded thousands of Mainers of the same thing—that there’d be no political or moral inconsistency in voting for Collins in 2014 and against her in 2020. The times have changed; Collins has changed. Maine’s voters have changed, too.

Correction, Sept. 8, 2020: This article originally misstated that Mainers ousted Republican Gov. Paul LePage in 2018. He was term limited, but voters flipped the governorship from red to blue.